Post by John Michael

One of the dilemmas that people face when switching to the Paleo diet is an apparent loss of variety in what they can eat. By becoming Paleo, we leave behind a great number of foods that human ingenuity has fashioned from the products of the agricultural revolution; whether it’s the grain-based cereals that we’ve become accustomed to eating in the morning, or the dairy-based desserts that send us off to bed at night, there’s a lot we leave behind. But, in my experience switching to the Paleo Diet, I’ve found that, instead of having my culinary horizons narrowed, this diet has actually revealed to me the great number of foods and flavors that exist outside of the realms of grains, dairy products, and heavily processed foods. These blogs, which will all be entitled Paleo Foods, are an attempt to share the diversity of delightful flavors that can be found within the alimentary domains of fruits, vegetables, meats, and nuts and oils, which together form the basic components of the Paleo Diet.

Anticuchos

A traditional Peruvian dish, anticuchos consist of cow heart sliced into knuckle-sized portions, and then spit and roasted on slender wooden skewers. When I ordered my first anticuchos at a restaurant in Lima, I found them to be of a tender and almost spongy consistency, although they were in no way chewy.

A traditional Peruvian dish, anticuchos consist of cow heart sliced into knuckle-sized portions, and then spit and roasted on slender wooden skewers. When I ordered my first anticuchos at a restaurant in Lima, I found them to be of a tender and almost spongy consistency, although they were in no way chewy.

As I ate, their rich flavor dominated my tongue, causing a faint tingling sensation that stopped just before it reached the threshold of stinging. There was also a slight bitterness to the meat, which I associated with the blood that must have once suffused this highly perfuse organ. All in all, the anticuchos had a savory, somewhat salty flavor. After eating the four pieces of meat on my two skewers, I found myself pleasantly satisfied.

Anticucho kebabs represent the standard Peruvian preparation of beef heart, and cooks here often embellish this meat with a glaze of their own devising. In my hostel in Lima, the kitchen was rather spare, so I decided to pan-fry my anticuchos, first searing them on high heat with a bit of vegetable oil, and then lowering the heat and tossing in chopped broccoli and carrots, along with diced garlic. Preparation time was between fifteen to twenty minutes, or until the meat was cooked and the vegetables were crunchy without retaining any rawness.

Regarding nutritional value, Calorie Count states that beef heart is “low in sodium,” while being high in “iron, niacin, phosphorus, riboflavin, selenium, vitamin B12, and zinc,” although the site also warns that beef heart is “very high in cholesterol.” I found the meat to be rich and hearty, and, after eating my anticuchos, I was left feeling energized to face the day.

Ceviche

I made my first ceviche with two traveling musicians from Chile. One of them, Camilo, had studied culinary arts for two years, so he led our endeavors. “There’s a wealth of ceviche varieties,” he told me as we prepared the ingredients, “but the basic idea is fish and lemon.” He paused, knife in hand, and then he added, “Think of it as ‘fish salad.”

I made my first ceviche with two traveling musicians from Chile. One of them, Camilo, had studied culinary arts for two years, so he led our endeavors. “There’s a wealth of ceviche varieties,” he told me as we prepared the ingredients, “but the basic idea is fish and lemon.” He paused, knife in hand, and then he added, “Think of it as ‘fish salad.”

Before us were two red onions, eight limes, a thumb-sized ginger root, three sea bass filets, and two different Peruvian hot peppers: one yellow pepper, and one rocoto. Together this would make enough ceviche for four or five. We began by shredding the ginger and cubing the sea bass filets, and then dicing the peppers and onions, while Grechio, Camilio’s travel companion, squeezed lime juice into a glass. The doorman at our hostel, in passing, remarked that it was strange to see people making ceviche at night, and when we asked him why, he responded, “Because it’s usually eaten in the morning, when the fish is freshest.” Once we had cut everything, we mixed it together with the lime juice in a casserole dish, adding only just as much diced hot pepper as tasted right. Then we put it in the fridge, where we left it for about half an hour, until it was sufficiently chilled. After a dusting of salt over the top, and a final mixing, we all sat down at the table, and shared our first Peruvian ceviche.

The smooth and soft taste of the sea bass was heightened by the other ingredients, whose sharp, citrusy, and spicy flavors provided an opposite extreme for the muted flavor of the bass, while the ginger tingled in the background, unexpectedly uniting the entire dish. The consistency was complex, with the soft flesh of the raw fish parting between our teeth easily, as the vegetables, although small, provided a welcome crunch. “I always use white fish,” Camilo told me as we ate, “because salmon is too greasy.” The ceviche was surprisingly delicious; the exterior of the bass cubes carried the complex flavors of the lemon juice, the onions, the ginger, and the peppers, while the interior of the fish maintained its exquisite natural taste.

The smooth and soft taste of the sea bass was heightened by the other ingredients, whose sharp, citrusy, and spicy flavors provided an opposite extreme for the muted flavor of the bass, while the ginger tingled in the background, unexpectedly uniting the entire dish. The consistency was complex, with the soft flesh of the raw fish parting between our teeth easily, as the vegetables, although small, provided a welcome crunch. “I always use white fish,” Camilo told me as we ate, “because salmon is too greasy.” The ceviche was surprisingly delicious; the exterior of the bass cubes carried the complex flavors of the lemon juice, the onions, the ginger, and the peppers, while the interior of the fish maintained its exquisite natural taste.

After finishing, we were all surprised to find ourselves exceptionally full without having overeaten, a fact that Camilo explained to me by saying, “Raw foods fill you with greater ease because they’re harder to digest.” And when I woke up the next morning, I was still far from hungry, even though over ten hours had passed since eating the ceviche. While I’m usually an early-starter, on that day I laid in bed for a while, and, free of my usual, “Where’s the food?” anxiety, I contemplated my life.

Huevos de Cordoniz

I first ate huevos de cordoniz, or, quail eggs, in Melgar, a warm-weather resort town three hours north of Bogotá. Discovering them alongside side items like French fries and mini-hotdogs, I indulged my curiosity, and ordered a portion. They came in a paper cup, around twelve or fifteen of what looked like miniature hard-boiled chicken eggs, and were slathered in ketchup and mayonnaise. (This was before I became 100% Paleo.)

I first ate huevos de cordoniz, or, quail eggs, in Melgar, a warm-weather resort town three hours north of Bogotá. Discovering them alongside side items like French fries and mini-hotdogs, I indulged my curiosity, and ordered a portion. They came in a paper cup, around twelve or fifteen of what looked like miniature hard-boiled chicken eggs, and were slathered in ketchup and mayonnaise. (This was before I became 100% Paleo.)

My first time eating them, condiments had hidden the huevos de cordoniz’s true flavor, so when I saw a shelf lined with plastic cases containing quail eggs in a supermarket in Lima, Peru, I decided to give them another try. Instead of hard-boiling them, I opted to fry them, sunny-side up, so I could get a better idea of how they tasted.

The first thing that I noticed was that cracking quail eggs was harder than I’d expected. The shells were more fragile than a chicken’s, and tended to crumble into fragments instead of cracking more or less evenly. Then, once the shell was cracked, there was a rubbery white membrane that I had to pierce so the egg could spill out. Once they hit the pan, the quail eggs fried rather quickly, though I soon saw that it would take at least five or six of them to match the amount of meat in just one chicken egg.

The first thing that I noticed was that cracking quail eggs was harder than I’d expected. The shells were more fragile than a chicken’s, and tended to crumble into fragments instead of cracking more or less evenly. Then, once the shell was cracked, there was a rubbery white membrane that I had to pierce so the egg could spill out. Once they hit the pan, the quail eggs fried rather quickly, though I soon saw that it would take at least five or six of them to match the amount of meat in just one chicken egg.

The quail eggs tasted much like chicken eggs, although I found their flavor to be richer and creamier, and, perhaps to an extent, gamey. They had a richness that was delicately complex; overall, I would call theirs a refined flavor. Their only downside was that there was so little meat in each egg.

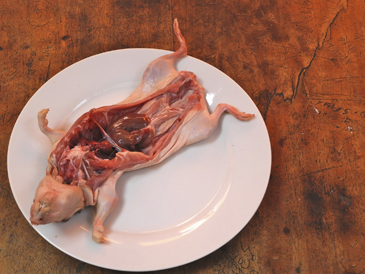

Cuy

“How can you travel the Andes and not eat cuy?” This was what I asked myself, as I stood in the Mercado Surquello, a large vegetable market in Lima, and looked at a woven basket within which were set three guinea pig carcasses. I had wanted to try cuy since friends in Bogotá told me that in the south, people ate guinea pigs, although, as I stood there looking at the basketful of slaughtered rodents, I began to ask myself why.

“How can you travel the Andes and not eat cuy?” This was what I asked myself, as I stood in the Mercado Surquello, a large vegetable market in Lima, and looked at a woven basket within which were set three guinea pig carcasses. I had wanted to try cuy since friends in Bogotá told me that in the south, people ate guinea pigs, although, as I stood there looking at the basketful of slaughtered rodents, I began to ask myself why.

Reservations aside, I decided to purchase a cuy. When I set myself to preparing the carcass, I was somewhat revolted, because I had the entire animal below my knife – all that had been removed prior to my purchasing it was its fur – and as I peeled away its skin, and then quartered it, I felt a deep welling of empathy for the creature, and an amount of sadness that its fate had been to end up on my cutting board. Working with the cuy became an almost spiritual experience, leading me to contemplate the chain of life that led between it and myself, and then continued beyond us.

I have to say though that this experience affected my meal, because, while I found the cuy’s flavor to be quite nice, somewhat like chicken, but lighter, with less strength to its taste, I couldn’t shake the image of the guinea pig from my mind as I ate. Perhaps it was the fact that I had cleaned the animal carcass myself, and I’m accustomed to faceless meat that my heart and mind don’t have to connect with the animal from which it came. The fact that guinea pigs are endearing and docile animals that are kept as pets in the United States also no doubt played a role in affecting my experience. What I do know for sure is that while the cuy was very delicious, I don’t think I’ll be eating another one any time soon.

I have to say though that this experience affected my meal, because, while I found the cuy’s flavor to be quite nice, somewhat like chicken, but lighter, with less strength to its taste, I couldn’t shake the image of the guinea pig from my mind as I ate. Perhaps it was the fact that I had cleaned the animal carcass myself, and I’m accustomed to faceless meat that my heart and mind don’t have to connect with the animal from which it came. The fact that guinea pigs are endearing and docile animals that are kept as pets in the United States also no doubt played a role in affecting my experience. What I do know for sure is that while the cuy was very delicious, I don’t think I’ll be eating another one any time soon.