Hominins selected “healthy” places to live 500,000 to 100,000 years ago

Sunday, December 22, 2013 at 02:24PM

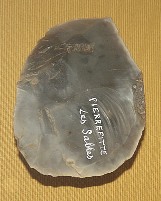

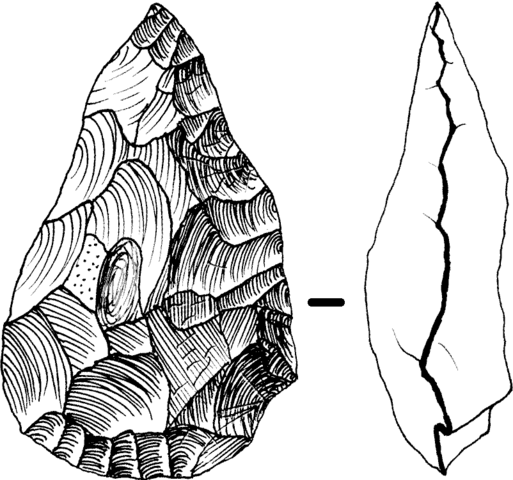

Sunday, December 22, 2013 at 02:24PM  Paleolithic handaxe. Image: José-Manuel Benito

Paleolithic handaxe. Image: José-Manuel Benito

There was plenty of real estate available in the Paleolithic. Hominins and early Homo sapiens probably choose sites according to many factors. Those choosing sites providing better nutritional opportunities were more likely to survive and create new generations.

The handaxe was an advanced Paleolithic tool used in procuring meat and tubers. By analyzing archeological sites on the British and French sides of the English Channel with a high number of handaxes (500 or more), researchers from the University of Southampton identified the types of sites preferred by hominins. Peter Franklin of University of Southampton writes:

“The high concentration of these artefacts suggests significant activity at the sites and that they were regularly used by early hominins.”

Lead author Professor Tony Brown, a physical geographer at the University of Southampton, commented on the study:

"Our research suggests that floodplain zones closer to the mouth of a river provided the ideal place for hominin activity, rather than forested slopes, plateaus or estuaries.

The floodplains provided "seasonal macronutrient advantages" and "could have provided foods rich in key micronutrients, which are linked to better health, the maintenance of fertility and minimization of infant mortality."

Professor Brown on the healthy nature of these sites:

"We can speculate that these types of locations were seen as 'healthy' or 'good' places to live which hominins revisited on a regular basis. If this is the case, the sites may have provided 'nodal points' or base camps along nutrient-rich route-ways through the Palaeolithic landscape, allowing early humans to explore northwards to more challenging environments."

Sources:

- Nutrients in food vital to location of early human settlements

- Site Distribution at the Edge of the Palaeolithic World: A Nutritional Niche Approach

Related Posts