Becoming Paleo, Part 4: The Projections of Anxiety

Saturday, July 2, 2011 at 06:42AM

Saturday, July 2, 2011 at 06:42AM  The projections presented junk food as the only way to escape the anxiety that was growing within me.”Post by John Michael

The projections presented junk food as the only way to escape the anxiety that was growing within me.”Post by John Michael

For the next two months after my day of fasting, I studied my eating problem. I had a basic understanding of the mechanism that underlie it: my mind would recognize a dilemma, which I would choose to ignore instead of resolving, thereby repressing the dilemma, which would then return to my consciousness as an image of food that I would be driven to attain to soothe a growing anxiety. But in order to solve this problem, I would need a deeper understanding of it.

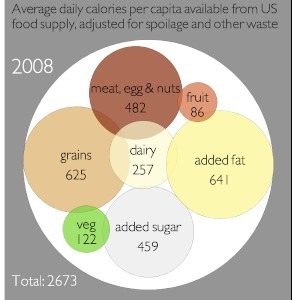

The projections were images of food, generally calorie-rich industrial foods, composed of a mix of flour, sugar, milk, or fat, if not all four of these ingredients. These images always had a will-violating quality: no matter how hard I tried to resist them, their power, in the form of anxiety, would only grow, until my will was overcome, and I found myself seeking out the food that they presented. I decided to begin my investigation at the root of this problem, with the issues that I was repressing by ignoring them when they appeared in my mind.

Under examination, all of these issues appeared related to one another by a theme of health. When the statement, “I am going to be alone tonight,” emerged in my consciousness, it was propelled there by a concern for my health, because, to my own mind at least, human contact is necessary for a healthy life. I repressed this thought by ignoring it as a nuisance, and so, because I hadn’t recognized the legitimacy of its concern, I unwittingly activated the projections of anxiety. It appears then that my mind contains an instinctual concern for my overall health, and that when I ignore my responsibility to both recognize this instinct and act in accordance with its concern, its frustrated psychic energy returns to my unconscious mind, where it animates the mechanism that transmits the projections of anxiety into my consciousness.

Though aware that the following is purely speculation, I would like to suggest an evolutionary rationale for this mechanism. A human being who ignores his instinctual concern for his health and the health of others predisposes himself to be less connected to his social group, because, by not caring for himself attentively, in accordance with his instinct, he can probably contribute less to the group, and because, by not caring for the members of his group as his instinct suggests, he probably reduces the group’s cohesion, at the very least with regards to his own social position. Basically, if you don’t pay attention to both your own health and that of others, you can offer less both to yourself and to your society, and will likely enjoy less of the survival advantages conferred by cooperation, in both its intra- and interpersonal forms. Without cooperation, the chances that I will go hungry in a hunter-gatherer milieu, like the one in which our ancestors evolved this instinct, increase, so the projections of anxiety activate, driving me to eat calorie-rich foods in an attempt to compensate for my reduced chances of survival.

This instinctual process, over which I should have had control, but which my willful ignorance had repressed, forcing it back into my unconscious, where it became automatized in its negative aspect, was living my life for me, but in a way that was contrary to my plans, by forcing me to act in accordance with it. Because I was content to ignore my health instinct, swatting it from my consciousness when it first appeared, as if it were an annoying house fly, it returned to my consciousness with a vengeance, and without regard for my volition, because, by ignoring it when it originally appeared, I had proven that my ego was ignorant of its responsibility to the other parts of my mind, and unaware of its position as conductor in the great mental orchestra of my thought. In its second appearance, the psychic energy of the health instinct had shed its cooperative aspect, and had become implacably coercive. It would be listened to, whether I wanted to hear it or not.

Stay tuned for Becoming Paleo, Part 5: Transforming the Projections of Anxiety.

Related Posts

Becoming Paleo, Part 1: The Yale Food Addiction Scale

Becoming Paleo, Part 2: The Anxiety Barrier

Becoming Paleo, Part 3: Breaking the Anxiety Barrier