Post by John Michael

Teepee and Cotopaxi: A teepee, which is part of the housing at Comuna de Rhiannon, sits in the foreground, while volcano Cotopaxi looms behind.

Teepee and Cotopaxi: A teepee, which is part of the housing at Comuna de Rhiannon, sits in the foreground, while volcano Cotopaxi looms behind.

There are many opportunities to create systems that work from the elements and technologies that exist. Perhaps we should do nothing else for the next century but apply our knowledge. We already know how to build, maintain, and inhabit sustainable systems. Every essential problem is solved, but in the everyday life of people this is hardly apparent.

Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual by Bill Mollison

I’ve heard a lot about sustainability, and I know that it’s a good thing, but I’ve rarely seen it in practice, and never to the extent that it’s practiced here, at Comuna de Rhiannon, a farming commune located within the Andes Mountains, and about an hour to the north of the Ecuadorian capital of Quito. Sustainability is the operating idea at Comuna de Rhiannon, and it governs the fate of everything that lives within the commune’s boundaries, from the hogs that are used to till Rhiannon’s soil, which is rich in volcanic ash, as the farm is surrounded by several volcanoes, to the food that is leftover from meals, which is either used as animal feed or as compost, depending upon what it is. Sustainability is such an integral part of the culture at Comuna de Rhiannon that on my third day here I found myself being teased by two young British men, who were residents of the commune at the time, because I had double-spaced my texts before printing them, and because I did not print on both sides of a sheet of paper. “That’s not at all sustainable, John,” chided Will. “No, absolutely not,” agreed Rob, who punctuated his statement by shaking his head in tongue-in-cheek disappointment. But, instead of reacting with annoyance, as I tend to do when I’m teased, I was pleasantly intrigued by the exchange, because it was the first time that I’d ever been teased about my sustainability. In fact, it was the first time that I’d ever heard of anyone being teased about their sustainability, and I began to wonder whether the culture of sustainability on display at Comuna de Rhiannon was a sign of the things to come in both Western Culture and, perhaps, Global Culture at large.

Click to read more ...

Friday, September 7, 2012 at 08:03PM

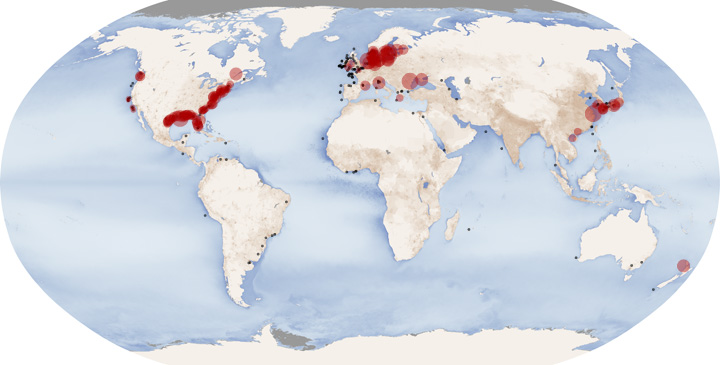

Friday, September 7, 2012 at 08:03PM  Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Image: NASA Earth Observatory organic farming,

organic farming,  organic food in

organic food in  Nutrition

Nutrition