Becoming Paleo, Part 2: The Anxiety Barrier

Saturday, June 18, 2011 at 02:05PM

Saturday, June 18, 2011 at 02:05PM

Post by John Michael

If taking control of my eating habits were something easy to accomplish, then I would have stopped consuming cheeseburgers and brownies years ago. But the truth is that gaining control of our diets is often a difficult thing to do, requiring a measure of self-will and discipline that nowadays might be called out of the ordinary, if not simply extraordinary. Taking this into account, my transition from the Standard American Diet (SAD) to the Paleo Diet was not an overnight affair, but instead the culmination of several small efforts that I enacted over the course of two years.

If I had to point to where this transformation started, then I would say that it all began with my yoga practice. I had practiced yoga for several years, trying various styles, from sauna-like sessions of Bikram Yoga, to methodical and in-depth Iyengar classes, but it wasn’t until I began attending Abhyasa Yoga Center in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, that I found the style of yoga which most suited me. The owner of this studio, J. Brown, had a simple philosophy, “Do what feels right,” which allowed me to strengthen my connection to both my mind and body, and so opened to me the possibility of real personal change.

J.’s philosophy, which he shared with me in a clear and accessible manner, while illustrating points with examples from his personal experience, was composed of variations on the yogic principle of ahimsa, or, non-injury. It doesn’t matter how you look in a pose, J. would tell me; what matters is how you feel. He once shared with me the story of how he had discovered this philosophy: he was an avid practitioner, who could do amazing poses and was often asked to demonstrate them for other students, but who found himself suffering from chronic pain that only increased. One day, he traveled to India to deepen his knowledge of yoga, where he met a swami with whom he decided to study. The swami, after asking him to narrate what he was doing in a certain pose, cut short J.’s long-winded description of his body’s anatomical positioning, and asked him, “Yes, but how do you feel?” The moment was an epiphany for J. From then on, the basis of his practice would not be meeting a pose’s requirements, but the extent that his body could comfortably enter the pose, which he gauged by paying close attention to how he felt.

Using measured breathing to calm myself, I gently entered each pose, directing my attention to both the exterior position of my body, and to the interior disposition of my feelings. As happens with all new habits, the emotional sensibility that I developed within the yoga studio began to appear in my daily life. Yoga, as J. had said, can happen anywhere, at any time. I soon found myself paying close attention to the emotional responses that I had to everyday situations, like waiting in the checkout line at the grocery store, or dealing with an unruly student in the classroom. My yoga practice at Abhyasa had started me down the path of addressing the severe self-awareness deficit that I had developed by watching television, playing video games, and performing other sedentary, and, in my case at least, stupefying activities.

I began to do an inventory of my feelings, for the first time ever getting concrete definitions for emotions like fear, anger, and shame. As my knowledge of these lower emotions grew, I began to experiment with changing them into their higher transformations: fear became courage, anger peace, and shame compassion. After about a year of self-study, I managed to quit smoking and limit my drinking. Things were going well, and I was pleased with my progress. But when I tried to control my eating habits, which were rather bad, often taking me off of my normal route to work in search of just the right chocolate bar, or causing me to eat a pint of frozen yogurt (sometimes two) per night for weeks on end, I failed miserably.

Each time I’d try to alter my eating habits, the same thing would happen: as the duration of my resistance to the cravings increased, I would feel anxiety building within me, a kind of jittery, unpleasant energy, that would grow until it cracked my will power, at which point I’d find myself driven out of my apartment in search of whatever junk food my mind presented to me as the best way of soothing myself. No matter how many times I attempted to stop my poor eating, I encountered this same emotional reaction, which I came to call the anxiety barrier.

Stay tuned for Becoming Paleo, Part 3: Breaking the Anxiety Barrier.

Related Posts

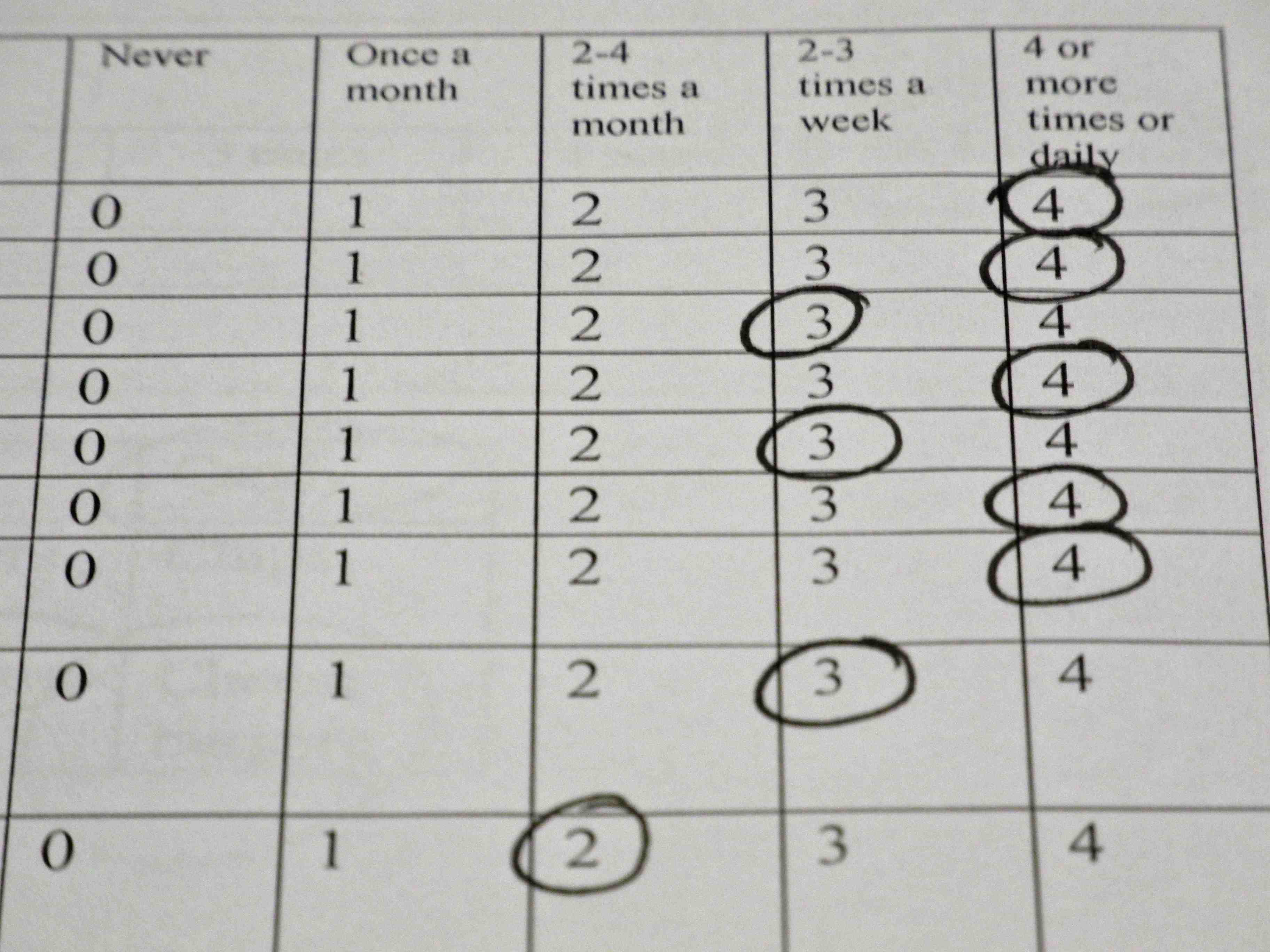

Becoming Paleo, Part 1: The Yale Food Addiction Scale

Becoming Paleo, Part 3: Breaking the Anxiety Barrier

Becoming Paleo, Part 4: The Projections of Anxiety

Anxiety,

Anxiety,  Paleo diet,

Paleo diet,  Yoga in

Yoga in  Nutrition

Nutrition