Controversy: Is cancer man-made?

Friday, October 22, 2010 at 12:58PM

Friday, October 22, 2010 at 12:58PM Recently, a press release on the scarcity of cancer in Egyptian mummies caused a stir on some news sites. As Tom Chivers, of Telegraph.com.uk, writes:

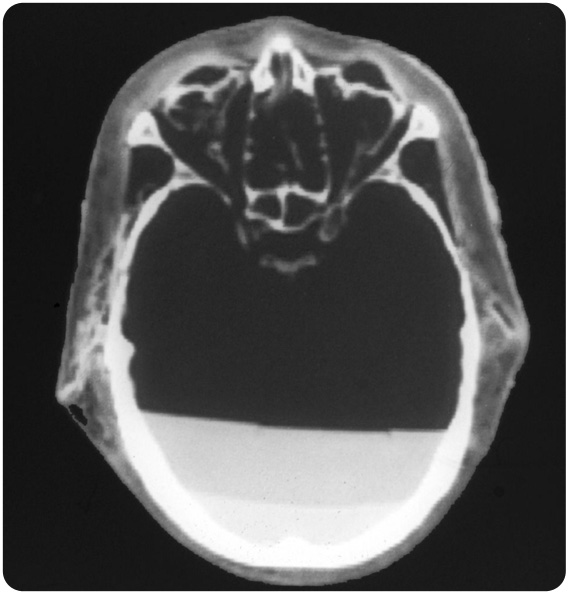

Egyptian mummy undergoing a CT scan. (Not part of the study). CyberMed, LLC Images

Egyptian mummy undergoing a CT scan. (Not part of the study). CyberMed, LLC Images

Now, I want to make it clear, we – and other papers – are not over-reporting this, at least in one sense. The press release from the University of Manchester is fairly unambiguous: “Scientists suggest that cancer is purely man-made“, says the headline.

While not a surprising conclusion to some, apparently, according to Andy Coghlan, cancer charities and cancer research organizations “are not happy”. The article in question, Cancer: an old disease, a new disease or something in between? by A. Rosalie David and Michael R. Zimmerman, was published this October in Nature Reviews. Dr. David summarizes their conclusions in the press release:

Yet again extensive ancient Egyptian data, along with other data from across the millennia, has given modern society a clear message – cancer is man-made and something that we can and should address.

So, is cancer “purely man-made?” Did the authors overstate the evidence and make claims that are “false and misleading?”

Evidence

David and Zimmerman present the paleopathological, literary and mummy evidence of cancer in antiquity. Let’s briefly look at these separately:

Paleopathology

Although the authors note that “various malignancies have been reported in non-human primates”, they identify only two reported tumor cases in hominid fossils:

1. In a study of “thousands” of bones belong to Neanderthal only one specimen (35,000 BP) revealed “a lesion (new bone formation) that might be related to a neoplasm — possibly a meningioma.” (A meningioma is a benign tumor of the brain or spine that in some cases thickens the skull in a characteristic pattern.)

2. A tumor “in the femur of the first Homo erectus fossil … is probably not a cancer but a benign bony proliferation and has been diagnosed as myositis ossificans (bone tissue that is generated in muscle tissue as a result of trauma and haemorrhage) or as an example of fluorosis.”

Literary evidence

According to the authors, a review of Egyptian papyri shows only “a few tenuous references to the disease.”

During the mummification process, the brain of the deceased was removed through the nose and resin was inserted resin into the cranium. This cranial CT scan of the mummy pictured above shows the resin settled in the posterior cranium. CyberMed, LLC Images Mummy evidence

During the mummification process, the brain of the deceased was removed through the nose and resin was inserted resin into the cranium. This cranial CT scan of the mummy pictured above shows the resin settled in the posterior cranium. CyberMed, LLC Images Mummy evidence

The mummy evidence is as follows:

• In 1967, PH Gray found no radiologic evidence of cancer in 133 Egyptian mummies studied

• In 2003, MR Zimmerman reported a histologically confirmed carcinoma of the rectum in an Egyptian mummy

Critiques

Critiques of the article primarily focus on three areas: limited evidence, average life expectancy, and natural causes of cancer:

Limited evidence

The paucity of literary evidence of cancer in Egyptian antiquity could be due to the lack of recognition of cancer or to the loss of relevant relevant material (papyri). Another valid critique is the limited amount of specimens studied. Even the largest study of 133 Egyptian mummies is simply not enough (as noted below) to draw such a strong conclusion. There is also the difficulty in recognizing cancer if degraded specimens.

Average life expectancy

As Coghlan notes, “almost all the mummies and skeletons were of people who died before the age of 50” and, since cancer is much more common after age 50, many Egyptians may not have lived long enough to develop the disease. David and Zimmerman do acknowledge the “average lifespan of the wealthier classes was between 40 and 50 years,” and even lower (25 to 30 years) in the Egyptian “non-elite groups.” However, they counter that evidence of atherosclerosis, Paget’s disease, and arthritis in a number of mummies suggests “many individuals did live to a sufficiently advanced age.”

Nevertheless, the average life expectancy in Egypt from c.4000 BCE to c.400 CE was markedly shorter than today. Thus, David and Zimmerman emphasize primary bone tumors in the young: “tumours arising in bone primarily affect the young, so a similar pattern would be expected in ancient populations.” The problem with this statement is the current average annual incidence of malignant bone tumors in persons less than 20 years of age is 8.7 per million (reference). Thus, a study of 115,000 such mummies would be needed to find one bone tumor in a child.

Natural carcinogens

The sharpest criticism was reserved for this statement by Professor David: “There is nothing in the natural environment that can cause cancer.” The Cancer Research UK website responded “this is simply untrue” and presented examples of natural causes of cancer including the sun (“the single biggest cause of skin cancer worldwide”), bacteria & viruses (including papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein-Barr virus, and Helicobacter pylori) which cause a number of cancers, radon (a radioactive gas produced by granite rocks “that is thought to cause between 3 and 14 per cent of all lung cancers worldwide”), and naturally-occurring chemicals, many found in foods, molds or plants.

Conclusion

So, is cancer purely man-made? No, not purely. Did the authors overstate their case? Yes, as noted above. However, is cancer mostly man-made? Yes, it probably is. Smoking alone is thought to cause 1/4 of all cancer world-wide. Lifestyle choices such as poor nutrition, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol, and other factors are modern culprits and most, very controllable.

Cancer,

Cancer,  Egyptian mummy in

Egyptian mummy in  Modern Diseases

Modern Diseases

Reader Comments (2)

Read "Food and Western Disease" by Staffan Lindeberg. He believes that cancer is man made as it was absent in contemporary hunter gather tribes. He lists the foods that cause cancers and current research to back it up.

Thank you for your comment. You raise an important point that I mostly agree with. I agree that most of cancer is man-made and that there is plenty of evidence for this. My concern regarding the study above is the implication that “cancer is purely man-made”. This exceeds the evidence in the study.

Thanks for pointing the readers to Staffan Lindeberg’s new textbook, Food and Western Disease: Health and Nutrition from an Evolutionary Perspective. I looked at my copy and agree with his comment in the Cancer section: “Within the field of paleopathology (the study of prehistoric diseases) there is wide agreement that metastasizing cancers are uncommon in the preagricultural skeletal remains.”

I agree that cancer in the Paleolithic was likely uncommon. Our sample size from this era is small making the likelihood of finding evidence low. Although a benign tumor, a meningioma has been identified in a Paleolithic skull from 32,500 years ago.

Humankind has always likely suffered from a low level of cancer that is not man-made. In the U.S. each year, about 5,000 cancer deaths occur due to background radiation, most often caused by radon gas emitted by soil and rocks such as granite. Also, sunlight is a “major contributor” to the development of melanoma.