Becoming Paleo, Part 5: Transforming The Projections of Anxiety

Saturday, July 9, 2011 at 10:23AM

Saturday, July 9, 2011 at 10:23AM  In order to be able to choose to eat the orange, instead of being driven to eat the cookies, I had to learn to listen to my health instinct.Post by John Michael

In order to be able to choose to eat the orange, instead of being driven to eat the cookies, I had to learn to listen to my health instinct.Post by John Michael

Addressing the problems of health when they appeared was all that it took to begin shutting down the projections of anxiety. So, for the original problem, “I will be alone tonight,” all that I had to do to prevent its repression was to commit myself to addressing it, thereby rousing myself from my ignorance, and expressing a willingness to know. This could have taken the form of seeking out a friend, or of merely appraising my situation in the light of my lack of friends; what was important was the perspective that I took, one that was oriented toward the problem’s solution – and when action was necessary, then I would have to act.

Although the transformation of anxiety was rather simple, it took me two months to learn how to do it, because I was dealing with poor eating habits that had been entrenched over several years, and, while it’s easy to realize that eating healthfully is good for you, it’s another thing entirely to reprogram your bad habits. But that’s what I was doing.

Shifting my perspective with regards to my health instinct from one of willful ignorance to one of cooperative curiosity did not mean that I had to be constantly on my toes; just like the ignorance that activated the projections of anxiety, after a while the willingness to know became habitual. But at first I had to pay close attention to myself, because the logic of this transformation is broad, and has different applications in various situations, though the underlying principle remains the same, which is that this instinct is concerned with my health and the health of those around me.

The logic of the transformation is quite simple: I can either take responsibility for my health, or I can ignore this responsibility. When I take responsibility, I observe the psychic contents arriving in my mind from the health instinct, and, noting their trajectory, I decide whether or not to act on them, and then how best to do so – though I have to be careful, because by not acting on them, I might repress them, and so activate the projections of anxiety. Which is to say that something has to be done with this energy, because if I ignore it, then I repress it, and it returns to my consciousness in the form of a compelling force, anxiety, which coerces my ego into doing what it presents.

Examination of my eating problem had led me to this, the fruit of my investigation, the realization that, if I allow myself to be ignorant of my health instinct, I get pushed around by it, and bullied into doing what it wants, but if I listen to it, then I can take control of my health, and nothing regarding it will happen without my consent, allowing me to guide the course of action proposed by this instinct, instead of falling under the merciless sway of the projections of anxiety.

Stay tuned for Becoming Paleo, Part 6: Implementing the Transformation

Related Posts

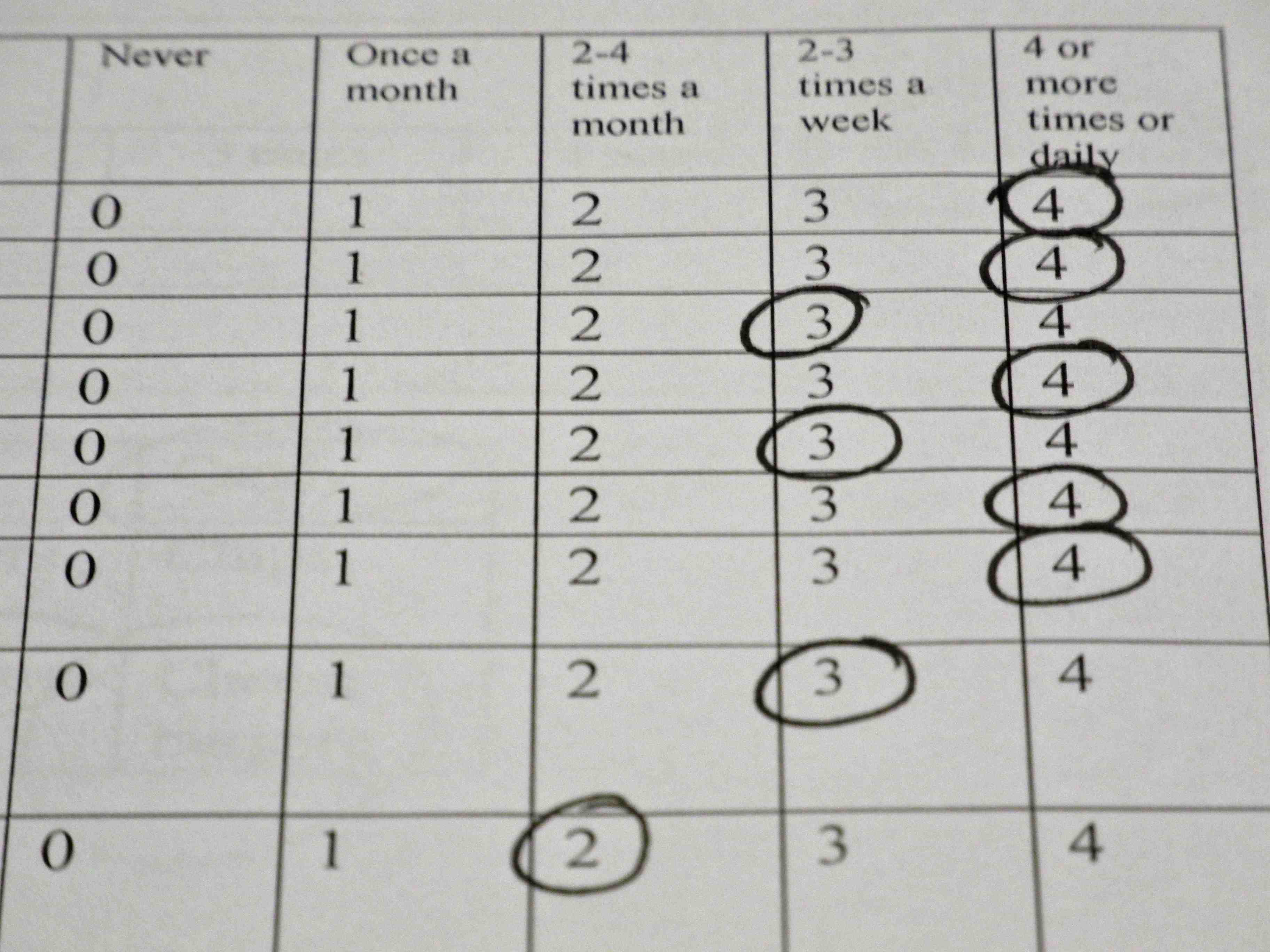

Becoming Paleo, Part 1: The Yale Food Addiction Scale

Becoming Paleo, Part 2: The Anxiety Barrier

Becoming Paleo, Part 3: Breaking the Anxiety Barrier

Becoming Paleo, Part 4: The Projections of Anxiety

John Michael is a traveling writer and a teacher with a deep interest in humankind’s connection to the natural world. Learn more.

John Michael is a traveling writer and a teacher with a deep interest in humankind’s connection to the natural world. Learn more.